On May 22nd we launch the “Jazz means Peace” series at the Bowery Poetry Club on the lower east side of Manhattan. The idea has plenty of surface appeal; we play music, collect some money, give some to a NYC based Peace Organization, pay the musicians and everybody has a good time and goes home happy. But there’s more to it than that.

On May 22nd we launch the “Jazz means Peace” series at the Bowery Poetry Club on the lower east side of Manhattan. The idea has plenty of surface appeal; we play music, collect some money, give some to a NYC based Peace Organization, pay the musicians and everybody has a good time and goes home happy. But there’s more to it than that.

The “Jazz Means Peace” series has a very simple game plan; It looks to bring together the jazz community and the progressive peace community and realize the synergy that will benefit both. It can generate a modest but regular flow of funds for peace organizations and at the same time develop an economic model for jazz and culture that is an alternative to the “entertainment business”.

Perhaps more important it tries to cultivate a relationship that can endure and become a regular part of the development of a “peace economy” that counters what America has become; a “war economy”. For this reason it shouldn’t be thought of as a fundraiser for peace organizations. Fundraisers are special events that attempt to raise as much money as possible in one big push. They rely very heavily on volunteerism to be successful. What we do is aimed at creating an economically viable and self sustainable structure. But we still need to answer the question “Why?”. Why does “Jazz mean peace?” That takes some reflection.

* * * * * * * *

I.] In my mind there is a difference between an “anti-war movement” and a “peace movement”. An anti-war movement is a reaction against a particular war, either in progress or imminent. Nothing else except opposition to that particular war needs to unite the people who participate in any organized expression of dissent. It is easier to motivate large numbers of people to take to the streets if they don’t have to share anything else with the people marching alongside them other than the desire to end the war. It’s a short term goal and it’s not necessary to share an analysis as to why the war exists, just the common objective of getting those in power to end it.

A peace movement is something different. It is more than the simple desire for peace. It has to address the more profound and abstract questions as to how and why we find ourselves in violent conflicts. A peace movement has to go beyond the material causes of war and of violence in general but must penetrate deeper and ask the fundamental question whether violence and war are unavoidable, the inevitable consequences of an inherent human condition. An answer seems elusive and history does not cheer the optimist. One thing we can be sure of is that we don’t have the comfort of certainty. What brings us to the point where we choose to believe that our actions do matter and that we do have the power to shape our own evolutionary direction is nothing less than a leap of faith. Despite so much around us that feeds despair and buries us in a suffocating confusion, it is the simple realization that no other choice is possible that makes the leap of faith obvious and easy. Suddenly the utopian becomes the pragmatic and the endless carnage of the centuries appears as just the madness of contaminated fantasies.

Shaping a human future free of the terrifying destructiveness of war is a complex multifaceted project that needs millions of initiatives and millions of leaders. It is a long term goal that requires patience and faith because progress is not always easily measurable. But if the rewards seem to come hard as if a dispensation from some stingy taskmaster in the sky, the hope and the vision make other pursuits seem just a frivolous waste of time. I come to this problem primarily as an artist, a musician, and in particular a jazz musician. What follows may seem like a useless digression but allow me this indulgence while I connect some dots.

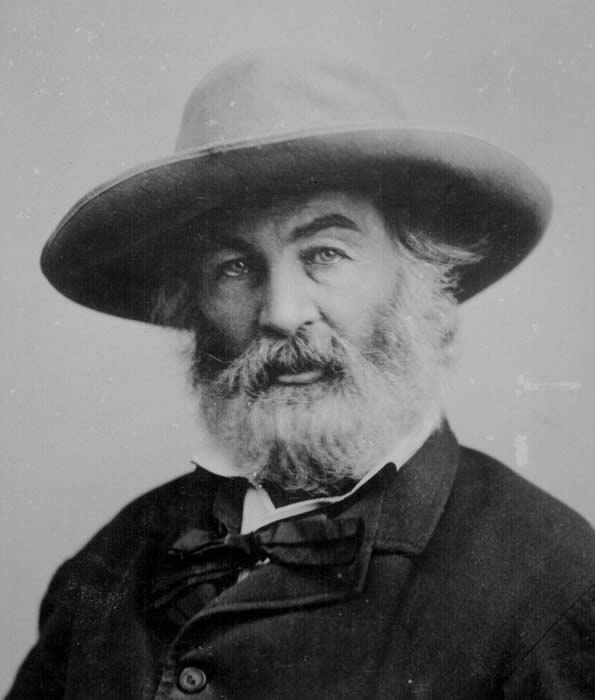

II.] Jazz music is now referred to as America’s “classical music”. It took a struggle to achieve that recognition and yet the art form suffers economically and spiritually more today than it did when it was considered the inferior product of “negroes” and “misfits”. To understand the significance of jazz in America it is useful to recall Walt Whitman.

In 1870, just five years after the Civil War, Whitman wrote a long essay entitled “Democratic Vistas”. Democracy had just survived its biggest test to that point but Whitman understood that while the country emerged intact, its noblest ideals seemingly vindicated in victory, slavery abolished and sufferage expanded, the country really had a far deeper challenge before it and the concept of democracy was as fragile as ever. The principal theme of his essay was that democracy was much more than a mode of political organization, it was an opening towards the development of a “new man” and as such it had to develop its own unique literature and arts. His harshest criticism was for those American writers who were imitating the aesthetic codes of aristocratic Europe and did not understand that it was much more than an ocean that separated the two continents. America was a new vision of reality.

“I say that democracy can never prove itself beyond cavil, until it founds and luxuriantly grows its own forms of art, poems, schools, theology, displacing all that exists, or that has been produced anywhere in the past, under opposite influences”. from Democratic Vistas

In fact America did begin to “grow its own forms of art”. Throughout the rest of the 19th century and the 20th century some of the world’s greatest writers emerged from the United States and a truly American literature was growing. Music, dance, and film would all follow suit. But something very important did not happen. While America was producing great writers whose vision was truly creating a unique American school of literature, the economic elite, the “ruling class”, did not embrace that vision and remained culturally either absent or in imitation of Europe’s old world aristocracy. A fissure developed between the intellectual and artistic worlds on one hand and the worlds of business and the “power elite”(1) on the other that would grow through the 20th century and become a huge gap. Some used the term “cultural lag”. The great body of America’s artistic heritage would now constitute an edifice of dissent, alienation, and resistance to the established order and the vision of those who wield power and make the decisions that bring us to war or to peace.

The idea that artists challenge social norms and provide a critique which marginalizes them does not sound controversial. Indeed it could even be argued that estrangement is the price one must be willing to pay. But the severity of the current divide is a relatively new phenomena. It wasn’t always so. Through the course of western culture artists and intellectuals certainly did criticize power, corruption and challenge aesthetic norms but generally it was within a shared sense of reality. (2) It wasn’t until the 19th century that the notion of the artist as an alienated bohemian, began to emerge. There was more or less a parallel development in Europe as well as in America but in the 20th century a combination of factors, from the dazzling success of mass advertising, consumerism, TV, Madison ave. PR and pop culture, the fissure becomes pathologically extreme in America. The “power elite”, those who really make the decisions on war and peace has remained culturally frozen in the era of 19th century monarchy and colonialism. It has never been comfortable living in the democracy they were born into and so Whitman’s vision of a grand “democratic civilization” is simply incomprehensible to them. They don’t know what that means.

The idea that artists challenge social norms and provide a critique which marginalizes them does not sound controversial. Indeed it could even be argued that estrangement is the price one must be willing to pay. But the severity of the current divide is a relatively new phenomena. It wasn’t always so. Through the course of western culture artists and intellectuals certainly did criticize power, corruption and challenge aesthetic norms but generally it was within a shared sense of reality. (2) It wasn’t until the 19th century that the notion of the artist as an alienated bohemian, began to emerge. There was more or less a parallel development in Europe as well as in America but in the 20th century a combination of factors, from the dazzling success of mass advertising, consumerism, TV, Madison ave. PR and pop culture, the fissure becomes pathologically extreme in America. The “power elite”, those who really make the decisions on war and peace has remained culturally frozen in the era of 19th century monarchy and colonialism. It has never been comfortable living in the democracy they were born into and so Whitman’s vision of a grand “democratic civilization” is simply incomprehensible to them. They don’t know what that means.

Power can do many things. One of the things that it can do is conceal forces in history and insulate a whole class of people from reality. Over the course of time this can lead to a condition similar to a schizophrenic detachment from the real world. It should not surprise anyone that the most hawkish enthusiasts for U.S. military action seem to come from that group of people most affectionately attached to the America of the late 19th century, its bourgeois culture and its ideas of social Darwinism. Ironically, unlike the business class of the 19th century, today’s corporate CEOs have usually graduated from business schools which have for the most part greatly weakened the old expectation of a “liberal education” that demanded at least a general familiarity with literature, philosophy, language, the fine arts, and history. Power through force and violence are all that is left to people whose world has long since vanished, succumbing to the natural social evolutionary process.

III.] It has been said that “artists are not really ahead of their time, most people are just behind theirs”.

At the polar opposite of the estranged “power elite” and its addiction to military force are the estranged artists who can reliably be found clamoring for peace. Why is this? Perhaps it’s because while the power elite is estranged from the natural organic flow of history, creating a conflictual tension within themselves and, by virtue of their enormous power, for everyone else, the cultural elite is estranged from that estrangement, but provided it is true to itself, it is not estranged from itself.

“America has yet morally and artistically originated nothing. She seems singularly unaware that the models of persons, books, manners, etc. appropriate for former conditions and for European lands, are but exiles and exotics here”. –from Democratic Vistas

It is the conventional wisdom that jazz had its birthplace in New Orleans Louisiana and then made its way up the Mississippi river to Chicago via the famous steam powered riverboats that hired bands to entertain the passengers at the turn of the last century. Some take issue with this narrative as overly simplistic but no one disputes that jazz was born in America. It is as original and organic to America as anything ever produced here and as un-European as anything Walt Whitman could have ever dreamed of. In fact with improvisation at the core of its aesthetic, it is the antithesis of the European fixed compositional genre.

It is the conventional wisdom that jazz had its birthplace in New Orleans Louisiana and then made its way up the Mississippi river to Chicago via the famous steam powered riverboats that hired bands to entertain the passengers at the turn of the last century. Some take issue with this narrative as overly simplistic but no one disputes that jazz was born in America. It is as original and organic to America as anything ever produced here and as un-European as anything Walt Whitman could have ever dreamed of. In fact with improvisation at the core of its aesthetic, it is the antithesis of the European fixed compositional genre.

So jazz means peace, right? Well, not exclusively jazz. But certainly the “arts”. When we talk about creating and sustaining a peace movement we are really talking about a social transformation that requires a cultural dimension. I believe that it is an essential and a peace movement cannot succeed without one. Transformation is a long range goal and one can argue that in the dynamic of democracy it is never really complete. Less conspicuous and euphoric than the anti-war movement, with its marches, demonstrations and theatrics, the peace movement works through a capillary presence in society slowly creating a foundation for transformation. It seeks to not just oppose war but to undermine the cultural and psychological constructs that give it support.

The politics of artists can gain great visibility in a variety of ways in the anti-war movement, by writing protest songs, painting bold murals, or performing at gala fundraisers etc.. The politics of artists in the peace movement are less perceptible, more subtle, but in the final analysis could be more profound. Maybe it’s even deeper than we think, or as one great poet expressed it…….

“Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration, the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present, the words which express what they understand not, the trumpets which sing to battle and feel not what they inspire: the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the World”. From “In Defence Of Poetry” Percy Bysshe Shelley; 1821

“Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration, the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present, the words which express what they understand not, the trumpets which sing to battle and feel not what they inspire: the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the World”. From “In Defence Of Poetry” Percy Bysshe Shelley; 1821

* * * * * * * *

1) C. Wright Mills 1916-1962 American sociologist coined the phrase “The Power Elite” and used it as the title of his most famous book.

2) Dante placed more than one Pope in the Inferno but he was a devout Catholic. Bach was a salaried composer for the church. Shakespeare was a commercial success. Mozart’s music was all performed while he was still alive. In fact most concerts from the 16th through 19th centuries were contemporary works. Only in the modern era have programs of classical music been dominated by composers long dead.